What is Market Microstructure and Why is it Useful?

Updated: 2017-10-06 11:31:52The market microstructure approach focuses attention on dispersed (often asymmetrical) information and how this information is aggregated into the marketplace. We always talk about sentiment as the current expectations of market participants regarding the future and the microstructure approach deals directly with how the order flow on a certain security influences the future dynamics of price. As such, understanding market microstructure is directly related to understanding order flow, with both tying into market sentiment.

While traditional technical analysis supports the “weak form” of the efficient market hypothesis, microstructure work has demonstrated how various groups of players actually have access to different information. All of this information is relevant but only a part of it is price sensitive. So when we speak about order flow from a microstructure perspective, we are speaking about informed transactions.

The role of private information

Important differences between the FX market structure and equity market structure

An inherent difference between the forex and equity markets is the nature and the sources of private information. In equity markets, private information relates to the fundamental value of equities, with tons of analysts bearing CFA certifications and in love with their spreadsheets doing the work. With this centralized order flow and disclosure, private information about order imbalance is quickly revealed, thus becoming public information and therefore no longer price sensitive.

There is a well-recognized information hierarchy from corporate insiders to institutional investors to individuals. Such an information hierarchy is critical to the standard models of price discovery where market makers don’t have private information and instead learn from trading against insiders.

When looking at currency markets, things are a bit different. To start, we have customers divided into two broad categories:

- Corporate clients (meaning firms that trade goods and services internationally)

- Financial customers (meaning primarily asset managers, smaller banks, and central banks)

Asset managers, in turn, are informally divided into two categories. First, we have unleveraged institutional asset managers (pension funds, mutual funds, and insurance firms), which are also commonly referred to as ‘real money'. Second, we have ‘leveraged money’ which consists of hedge funds and their close cousins, CTAs (commodity trading advisors).

FX trading is decentralized and opaque, so the short-term order flow imbalances are in fact private information and property of individual dealers. Academics have been accumulating evidence in the past decade that this order flow imbalance is an important determinant of exchange rate movements. FX dealers are not uninformed market makers as in the equity markets, but rather insiders with private information or non-fundamental speculators. Their private information comes from trading with their customers and other dealers. Some books and traders remind newcomers that the FX market is still geared towards the institutional clients and now you know exactly why.

![clip_image002[7] clip_image002[7]](/Assets/SunBlogNuke/5/WindowsLiveWriter/WhyisMarketMicrostructureUseful_8D6F/clip_image002%5B7%5D_thumb.png)

The FX food chain. Source: Beat the Forex Dealer/A.Silvani

Today’s dealers need not hold inventory until new customers arrive but can instead offload inventory quickly and at low cost in an active interdealer market. The share of interdealer trading, most recently estimated at 39% by the BIS, is comparable to the share on the London Stock Exchange and other liquid OTC markets with interdealer trading. Major dealers use the interdealer market for speculation as well as inventory management. The interdealer market is the core of the overall foreign exchange market in the sense that quotes to non-dealers are set as a spread on the current interdealer quotes.

Although some interdealer trading takes place via the regular OTC market, most now takes place over electronic limit-order markets where no one is formally assigned to provide liquidity. Instead, every participant chooses between supplying or demanding liquidity on a trade-by-trade basis. Liquidity suppliers post limit orders, which state the amount they are willing to trade, in which direction they wish to trade (buy or sell), and the worst price they will accept. Liquidity demanders post market orders, which state the amount they will purchase immediately at market, recognizing that they will get the best prices available from liquidity suppliers. A broker keeps track of these best available limit-order prices and matches them to arriving market orders.

![clip_image004[7] clip_image004[7]](/Assets/SunBlogNuke/5/WindowsLiveWriter/WhyisMarketMicrostructureUseful_8D6F/clip_image004%5B7%5D_thumb.png)

Reuters Dealing Screenshot (Source: Reuters/ChrisLori)

And what about the retail trader trying to work his edge in this environment? Electronic trading has created an entirely new type of platform, the “retail aggregator”, which in turn has introduced a new breed of currency trader: the small individual investor. Retail trading is difficult to measure but preliminary estimates suggest it has grown from negligible levels in 2001 to reach 10% of trading nowadays.

Revisiting the importance of Order Flow

Now that we have a good understanding about the structure and participants of the FX marketplace – and where they stand in the food chain – we can better grasp the importance of focusing on order flow dynamics. To explain the influence of order flow on exchange rates, economists tend to focus on three things:

- Currency trading is not cost-free: currency dealers charge a bid-ask spread. In the presence of such spreads, aggressive buying/selling automatically move the price up to the ask & down to the bid on average.

- Limits to arbitrage: currency trading is never unlimited, as dealers are constrained by position and loss limits, while asset managers and retail traders are constrained by funding constraints and risk aversion influences their psychological biases. If investors were risk neutral and could trade unlimited amounts of an asset, its price will only move in response to the arrival of new information. But rigorous evidence shows that currency prices move in response to non-informative shocks just like equities and bonds. Daily price moves are driven by the net demand shock from one set of customers and the supply elasticity of another. Moreover, these shocks come frequently from exogenous influences, like private information about future returns (cash flows), changed perceptions of risk (discount rates), or pure liquidity needs such as end-of-month inflows to retirement funds. Exogenous influences on corporate currency trading include domestic and foreign GDP, inflation, and barriers to trade. Exogenous influences on retail traders include private information (or perceived information, as discussed below) and pure liquidity needs.

- Asymmetric information: in equity markets, private information is gathered by armies of analysts who pore over financial reports, meet management, and visit competitors. The nature of private information in FX is less obvious, however, because currencies are largely driven by macroeconomic variables, such as prices, interest rates, and output, that are publicly announced. A role for private information emerges when we note that macroeconomic data are necessarily reported with a lag, so motivated traders might combine publicly available data about past macroeconomic conditions with their own insights to derive private estimates of current values. Market participants report that leveraged investors are especially active in this endeavor.

But more recently, academics suggest that private fundamental information is naturally dispersed among customers and that dealers can infer this information by observing patterns in order flow. Better business conditions and expanding internal demand, for example, automatically generate rising currency demand from manufacturing firms. A dealer could infer the economy’s underlying change in strength by observing that currency demand is consistently rising among importing firms. And because trades between dealers and customers are not revealed publicly, that dealer’s information would be private.

Whether customers aggressively seek information or passively reveal information through trading motivated by other factors, this perspective implies that customer order flow (in particular, speculative customers like hedge funds and CTAs) has predictive power for macro fundamentals and for future exchange rates. A critical consequence of this dynamic is a tendency of dealers to trade more aggressively after dealing with informed customers and this idea that informed agents are likely to trade aggressively is predicted in theoretical treatments of limit-order markets. After trading with an informed customer and learning that customer’s information, a currency dealer has two additional incentives to trade aggressively: the dealer has taken on the customer’s inventory and associated inventory risk, and the dealer’s information indicates that this inventory position is likely to incur a loss.

What is Order Flow and How Can Use Order Flow in Our Trading?

Order Flow vs. Supply & Demand; Is There a Relationship?

Order flow is defined as the cumulative flow of signed transactions. The sign (positive or negative) depends on whether the client (not the market maker/dealer/broker) is buying or selling. But order flow is not the same as demand or supply. Order flow measures actual transactions, whereas textbook supply and demand does not need any transactions whatsoever. In demand/supply models, shifts in macro fundamentals cause shifts in demand and thus price, but without any transactions taking place, or needing to take place, in order for the price change to occur. Demand is shifting but no order flow is occurring because at the new price people are indifferent again between buying and selling. Traditional economics come to odds with the actual functioning of the marketplace. These textbook models are unable to account for the strong positive correlations between signed order flow and the direction of price changes found in the data because they assume that all demand shifts are driven by changes in public information.

What can order flow low tell us, other than “price is going up” or “price is going down”?

Order flow is not just about volume, but actually plays two distinct roles: they clear markets and they convey information. The first role covers the simple “more buyers than sellers or vice-versa” view of why flows affect prices. We can see this day in and day out when watching asset price movements.

![clip_image006[7] clip_image006[7]](/Assets/SunBlogNuke/5/WindowsLiveWriter/WhyisMarketMicrostructureUseful_8D6F/clip_image006%5B7%5D_thumb.png)

Exemplifying the first role of order flow: supply/demand imbalance measure

The second role is deeper (and too often missed) and arises in contexts where information is dispersed because transaction flows affect people’s expectations (about future fundamentals and prices). This second role is even more relevant in the FX Market because academics have found that transactions have different effects on price, dollar for dollar, depending on the institution type behind them. Academics have also noted that transaction flows in one currency market have price effects in other currency markets, despite not occurring in those other markets.

The logical question would then be: If order flow is the dominant source of price movements, is there any other? There are many variables that can lead to shifts in the supply & demand function of the market, but so long as they are public information (like macroeconomic variables such as inflation, GDP, interest rates, etc.) then the price differences we observe take place quickly as participants take positions based on this public data. However, outside of those events, order flow can convey private information which is a whole other story.

Isn't order flow an endogenous part of the market and thus without predictive power?

Order flow is part of the market. But the variables used in traditional macro models (money, income, interest rates, etc.) are also endogenous variables. What microstructure theory provides is a means for understanding why signed order flow transactions can cause price movements, even if they're part of the same system. The reason has to do with information: as we have noted, order flow is correlated with information that is not known by all market participants. Order flow, then, is a proxy cause of exchange rate changes, with the underlying dispersed information being the primitive cause.

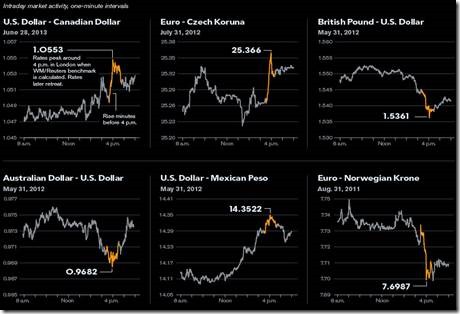

We’re currently going through a beautiful, real-world, hard-evidenced example of the level of importance of private information and order flow: the FX probe. Why are the regulators forcing bank traders out of chat rooms, voice squawks and other information-sharing vehicles? Because bank traders were sharing private information and then acting upon this information to manipulate the London Fix. Order flow can and does reveal the intentions of private information. Because if the information is available and seen as valid, it will be acted upon. And when it is acted upon, it pops up in the flow.

Manipulation of Price Action across the board at London Fix. Source: Bloomberg

But how can we ever learn what is behind the order flow, what is causing it?

In fact, the emerging literature offers many approaches to addressing this question. Examples include the following:

- Empirically, flow appears to serve as a kind of expectation “proxy” in the sense that it reflects individuals’ heterogeneous expectations about future macro variables, including an ability to forecast those variables;

- The arrival of macroeconomic news and central bank interventions has been shown to drive flow, perhaps because people’s exchange-rate expectations respond differently to the same data;

- The information content of flow has been shown to differ by source, leading to analysis of the types of information specific agent types might have;

- Trades in many major markets, like the EURUSD market, have been shown to convey information relevant for other rates, like the USDJPY. These cross-market results help identify the nature of the underlying information (whether it is $ specific, Euro specific or else).

![clip_image010[7] clip_image010[7]](/Assets/SunBlogNuke/5/WindowsLiveWriter/WhyisMarketMicrostructureUseful_8D6F/clip_image010%5B7%5D_thumb.png)

A visual representation of the cross-market results of order flow. Comparing USDJPY to its crosses. It’s evident that there is a common story affecting the JPY specifically.

Source: Beat the Forex Dealer – A. Silvani

To sum up: the microstructure (which as we have learned, means the participants and their roles) of the FX market is very different than other markets. The existence of private, dispersed information, makes order flow very important because it's only through the price discovery mechanism, i.e., through trading between informed and non-informed participants, that information is disseminated. Aggressive one-way flows from a non-quoting counterparty (large speculators) contain private information that can and does influence future exchange rate trajectory, because participants trade based on their expectations for future developments.

That's why it's imperative to trade in the direction of clear sentiment & flow. By learning to “read” the flows correctly, you will be trading in line with the informed players and, in a fashion, becoming an informed participant yourself.

References:

Bjønnes, G., and D. Rime, 2002, Volume, order flow and the FX market: Does it matter who you are? working paper, Stockholm Institute for Financial Research.

Cheung, Y., M. Chinn, and I. Marsh, 2000, How do UK-based foreign exchange dealers think their market operates, NBER working paper 7524, February

Evans, M., and R. Lyons, 2000, The Price Impact of Currency Trades: Implications for Intervention, working paper, U.C. Berkeley.

Evans, M., and R. Lyons, 2002a, Order Flow and Exchange Rate Dynamics, Journal of Political Economy 110: 170 – 180.

Evans, M., and R. Lyons, 2002b, Are Different-Currency Assets Imperfect Substitutes? working paper, U.C. Berkeley.

Evans, M., and R. Lyons, 2003, How Is Macro News Transmitted into Exchange Rates, NBER working paper 9433.

Goodhart, C., T. Ito, and R. Payne, 1996, One day in June 1993: A study of the working of the Reuters 2000-2 electronic foreign exchange trading system. In The microstructure of foreign exchange markets, edited by J. Frankel, G. Galli & A. Giovannini. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Osler CL. 2000. Support for resistance. FRBNY Econ. Policy Rev. 6(2):53–68

Osler CL. 2003. Currency orders and exchange-rate dynamics: an explanation for the predictive success of technical analysis. J. Finance 58:1791–819

Osler CL. 2005. Stop-loss orders and price cascades in currency markets. J. Int. Money Finance 24:219–41

Osler CL. 2009. Foreign exchange microstructure: a survey. In Encyclopedia of Complexity and System Science, ed. RA Meyers. New York: Springer